BERTJE IS CARELESS

Written by Bert Plomp

It was clear. Christian education wasn’t meant for me. My parents had finally reluctantly acknowledged that as well. They didn’t want to risk being ostracized by the Christian community due to my heathen behavior at school. For that reason, I was sent to a nearby public school.

The Hans Christiaan Andersen School had the honor of welcoming me as a student. This school was led by a certain Mr. J. Schlahmilch. His name suggested he had German blood, which in 1954 was still a touchy subject for many. But for me, Schlahmilch was simply a fantastic, dedicated, inspiring headmaster whom I greatly enjoyed. Moreover, I saw something of the ‘milky way’ in his name, which I had already embarked upon as an M-brigadier.

In the early fifties, the school was located on Adriaen van Ostadelaan, roughly halfway between Stadionlaan and the entrance to the former Rijksweg 22.

It was a charming, wooden temporary building with six classrooms. The classrooms at the front offered a view of a large, yellow-colored five-story apartment building, while those at the back overlooked the highway. A wide path ran between the school and the highway, and on game days, hordes of DOS supporters walked along it on their way to Galgenwaard.

The road always had a magnetic pull on me. The highway was elevated on a embankment, and cars sped by at high speeds. There was an air of danger around that road.

I still get anxious when I think back to the moment when our dog Marsha suddenly broke free and dashed up the embankment of the highway with her leash still attached. I ran after her as fast as I could, but unfortunately, I couldn’t prevent her from darting onto the road. She managed to reach the median unscathed amidst the passing cars. I didn’t dare call her back, fearing she would make that dangerous crossing again.

Once it was safe, I crossed the road myself and tried to grab her by the neck. But before I could catch her, she slipped through the median and blindly hurdled the second obstacle. Miraculously, she made it to the other side unharmed. Thankfully, I managed to grab her by the leash there and bring her home in one piece.

In the winter, when it snowed, the children from Napoleonplantsoen would flock to the embankment with their sleds. Once they reached the top, they would sit on their sleds and slide down. No parent seemed concerned that above, behind the children’s backs, cars were racing by at full speed. Nor did anyone worry that many children, at the bottom of the slope, would venture onto the slippery road without a care in the world.

In 1958, right next to the school, the Stadionflat was built. This building had ten floors and was one of the tallest residential towers in the country at the time.

I would often climb over the barrier and visit the construction site. There was always useful construction debris to find, like wood and plastic pipes. You could make a nice weapon out of these, like a rifle to blow paper darts.

Once the building was completed, I would frequently take the elevator to the top. From the top floor, you had a beautiful view of the stadium’s grassy field. In my imagination, I would score goals for DOS there and be cheered on from the stands.

The elevator ride up was often terrifying. The elevator was quite small, and the shaft was very deep. As a young boy, the thought of that combination would give me goosebumps.

Once I reached the top, standing on a narrow gallery separated from the bottomless abyss by a low wall, that uncomfortable feeling only intensified. If I then gazed down into the depths, a scary thought would sometimes cross my mind. I would wonder what it would feel like to plummet from that height and crash onto the pavement below. This strange, dizzying consideration would immediately send me rushing to the elevator to get back to the safe ground as quickly as possible.

What a great time I had at that school. This was largely due to the education the headmaster advocated and his immense involvement in everything happening at the school.

Schlahmilch didn’t just push the students for good academic results. He also encouraged them to participate in sports, acting, and creative activities.

Under his enthusiastic leadership, there was a lot of soccer played. With a half-burned cigar in his mouth, he even joined in himself, despite his advanced age and somewhat non-athletic appearance. He was rather tall and looked a bit frail.

Every year, he asked the students in the higher grades to come up with a play and perform it during the Christmas celebration. That was always a lot of fun.

Annual exhibitions were also organized. You would be paired with a classmate and given the task of creating something within a specific theme. So, my friend Joop and I made a wooden airplane, a boat, and a large diorama. The exhibition always coincided with a parents’ evening, so parents could see what else their children were capable of.

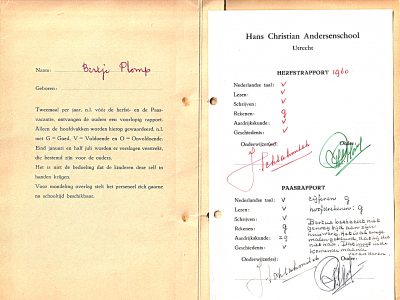

I still have a report book from the H.C. Andersen School detailing my progress there. Without any critical comments, it repeatedly pointed out that more attention should be given to my homework at home.

There were frequent mentions of the fact that Bertje reads too slowly. It was also noted that he is not only careless but spends the whole day gazing outside. The latter is still the case today. While I used to peer out of the school window at the free birds, now it’s my playing dogs and the wild Atlantic Ocean that capture my interest.

It was also believed that there was more potential in me than was being realized. I think that’s still true. I usually don’t exert myself more than strictly necessary.

The only one who acted on all the well-intentioned advice was me, but only when I felt like it.

Reading, writing, and language were highlighted in every report. My father and mother simply didn’t have the time to get involved. They were already busy earning a living to meet the basic needs.

A house with a separate, heated room for each child was an absolute luxury and unattainable at the time.