FROM COLLECTOR TO RESEARCHER

Written by Bert Plomp

In the past, whenever I could make some money, I was always at the forefront. With just a little pocket money per week, you couldn’t do much. You could buy two Mars bars and then wait until the next Saturday. I gathered some extra money in various ways. I had a paper route, helped shopkeepers with cleaning up and distributing advertisements, and collected rags and old paper. Additionally, I traded and sold stamps at the stamp market. For my stamp collection, I tried, literally and figuratively, to extract stamps from everywhere. I visited offices and shops to obtain used stamps. Every ’trash can day’, I was rummaging through the waste of companies, looking for stamps. Often, I had to tear the stamps off the envelopes first. Once I had gathered a substantial amount, I would soak them off the last piece of envelope. Then I placed the whole pile in a basin of hot water. After soaking overnight, I would lay the soaked stamps out to dry on an old newspaper. Once the stamps were dry, I carefully sorted them and placed them in my stamp albums.

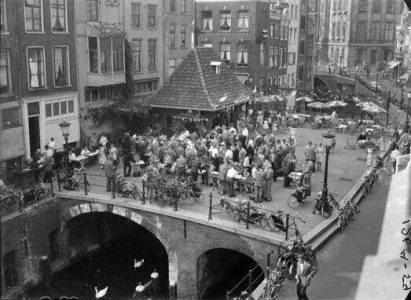

Every Saturday, you could find me at the stamp market. At the Vismarkt in Utrecht. There, I presented my stamp albums to potential buyers for inspection. Not all stamps went into those books. I made a distinction between stamps I deemed worth keeping for myself and stamps for sale. Every year, a new stamp catalogue would appear. In it, you could read how much your stamps were worth. What the prices were for stamped and unstamped stamps. Usually, unstamped stamps fetched more. However, occasionally, you paid considerably more for a stamped specimen. Almost all stamps increased in value each year. That’s why I enjoyed reassessing the value of my possessions time and time again. In the catalogue, my attention was mainly drawn to stamps with the most and highest digits before the decimal point. There were stamps worth a few thousand guilders. Unfortunately, those didn’t feature in my collection. The value of my stamps ranged from five cents to a guilder. Only a small number of stamps were worth more than a guilder. If I had made good deals on market days, the result was just enough to buy a large bag of fries with mayonnaise and a bottle of cola. I always did that. That way, I could exchange the entire day’s proceeds at a nearby cafeteria on the Oudegracht.

On Thursdays, it was usually ’trash can day’ in my neighbourhood. On that day, the municipal sanitation service would come thundering through the streets to empty the garbage cans parked on the sidewalk with a lot of noise. This usually happened after noon. Around the time I came home from school to have lunch. From the H.C. Andersen School on Adriaen van Ostade Lane, I always walked home via Israel Lane and Breitner Lane. Via Prinse Bridge, I finally crossed the river Kromme Rijn to Napoleon Plantsoen. The people who lived between my school and Prinse Bridge belonged to the affluent bourgeoisie. People from the better-paid class. They were directors, professors, doctors, and other persons of distinction. Unlike in my street, the trash cans of those residents often contained valuable discarded items. To get hold of them, it was important to scour all the bins like lightning. Preferably first. At least before the sanitation workers could strike. Fortunately, they didn’t suddenly appear in front of you. You could detect their impending arrival from a great distance by the deafening rattling of garbage cans.

I found all sorts of valuables on such hunts. Like still-usable toys, old books, and records. Not to mention the coveted envelopes with stamps. Once, I found a bundle of interesting magazines. Magazines full of images of naked, blonde, athletically built ladies of Germanic origin. I found this fascinating collection in the garbage can of a professor of ‘Topographical, Human Anatomy’. Not just any affluent person. That professor was engaged in the science that focuses on the shape, position, size, and proportion of the various structures of the healthy human body. Those magazines indeed contained many of those structures, positions, and forms of healthy women, I could ascertain with my own eyes. The fact that you could also earn a good living with such a study appealed to my imagination. After I had perused those booklets page by page, I envied the professor so much that I no longer thought about becoming an engineer. Since that day, I only dreamed of a future at the university. A future as a scientific researcher in the field of topographical, human anatomy. With a specialization in the female body. I never really understood why the professor had discarded such a beautiful collection as old junk. Had he perhaps, with government subsidy, managed to conquer new, healthy structures? Perhaps even three-dimensional ones?

TO BE CONTINUED

For all episodes, click on: Capital and labour

For more free stories, subscribe to my FB page: